Yes, I am disappointed. But depressed, demoralized, defeated? Not! This was a complex race with a lot of variables that make it hard to precisely analyze and arrive at specific conclusions. The campaign never had illusions about winning. Some thought it was possible, but perhaps not probable, that Chris could win. Others were not so sanguine, more realistic regarding the forces we were up against. Immersed in the campaign and believing in it, I, and many others, worked hard, very hard.

The night before the election at an Owens rally at the YWCA, peace activists Sam Koprak, Evelyn Abelson and Georgia Guida, pose with progressive Congresswoman Maxine Waters.

The night before the election at an Owens rally at the YWCA, peace activists Sam Koprak, Evelyn Abelson and Georgia Guida, pose with progressive Congresswoman Maxine Waters. Maxine and me.

Maxine and me. Three great, progressive members of Congress: Major Owens, Lynn Woolsey and Maxine Waters.

Three great, progressive members of Congress: Major Owens, Lynn Woolsey and Maxine Waters.More than anything else, this was a campaign that went up against the power of big money. The developers, like Ratner and others, have their eyes on Brooklyn. Those eyes have dollars signs in them. In yesterday's Times, an article about Atlantic Yards notes that "in Brooklyn ... candidates who had campaigned strongly against the project were defeated by candidates supporting it." But the story behind the story (the story the Times conveniently leaves out) is the part about big money and how it pollutes our country's politics. The favored candidate of the big developers, David Yassky, came in second (thanks to Chris' good performance in predominantly liberal, white Park Slope). His campaign was fueled by a war chest of $1.5 million (Chris raised a total of $300 thousand) and put out a dozen slick, glossy mailers in the course of the weeks leading up to the election. Never mentioning his support of Atlantic Yards, he pictured himself as an advocate of affordable housing and an crusader for peace, thus deluding unsophisticated voters that he was worthy of their vote. Yvette Clark, the African-American Councilwoman (and the victor in the election) also had money, remnants of the Brooklyn political machine and the power of Congressman Anthony Weiner's organization. She, too, campaigned as a fierce opponent of the war (not having been a leader on the peace issue during her tenure in the City Council) and kept mum on her support of the Ratner development which will surely wreak havoc on her constituents who are overwhelmingly poor and people of color as they are inevitably driven out of the area by gentrification and rising rents.

Add to the politics of big money, the disunity and yes, opportunism, among some leaders of the labor movement. Many unions threw their weight behind Clark and Carl Andrews, the other African-American in the race, sadly, deserting Chris, son of Major Owens who was, perhaps, labor's most steadfast friend in Congress. They opted, instead, to back a perceived "winner," rather than support the Owens candidacy, one that was genuinely progressive and unstintingly pro-labor.

A third big problem was the split in the Black community: three candidates campaigning for the African-American vote with a white interloper (Yassky) hoping to win on the back of that disunity. The Owens campaign did not have sufficient strength or organization in large parts of that community that, coupled with its very decent performance in the white neighborhoods, would have guaranteed victory.

Were there problems with the campaign itself? Of course. More money would have meant better organization, more literature, a more experienced staff, etc. But that's always a problem with a "people's" candidate who has to do battle against the well-endowed campaigns of the mainstream candidates backed by big business. The lesson to be learned here is that if we have to depend on people instead of money, then we better have lots of people. That means people in motion: a movement or movements. And that was the fourth big obstacle. While this section of Brooklyn is known as a bastion of liberal sentiments, that doesn't translate into powerful movements. Yes, we have a good and active peace movement. There is a strong organization that is fighting the Atlantic Yards, the skyscraper city that big real estate would impose on this neighborhood. And there are progressive Democratic party clubs that have been active here for years. It takes all of those and the power of labor as well to build a movement that can wield political power. In a previous post, during the height of the campaign, I complained about the lack of interest on the part of progressive activists in this campaign. I opined that progressives should have embraced this campaign as their own and put their blood and sweat into it. Some did, particularly those involved in the anti-Ratner movement. But many who should have, did not. Instad, they stood on the side and did not participate. There is a historic antipathy to electoral politics in the Left and I think the apathetic approach to the Chris Owens campaign demonstrates it very clearly. Many activists I spoke to were uninformed and very confused about the race and the various candidates, not seeing clearly the connection to big money or indeed to the very future of progressive politics in our community as wealther, more conservative forces move into Brooklyn and more dependably-progressive (poor and working class people and people of color) are forced out.

Ethel Owens (Chris's mom) outside PS 282 in Park Slope on election day.

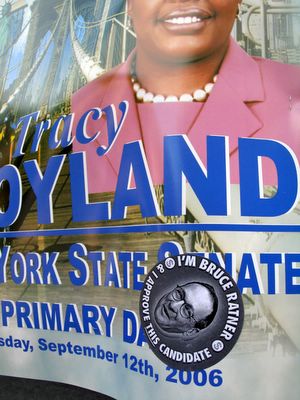

Ethel Owens (Chris's mom) outside PS 282 in Park Slope on election day. Someone stuck a perceptive sticker on a Boyland campaign poster. Untrammelled development was a big issue in this campaign. Chris, and a handful of other candidates, stood up to Ratner to defend the community. Most others accommodated themselves to the power of big money.

Someone stuck a perceptive sticker on a Boyland campaign poster. Untrammelled development was a big issue in this campaign. Chris, and a handful of other candidates, stood up to Ratner to defend the community. Most others accommodated themselves to the power of big money. On election day, I worked with my friend Bobby Greenberg and others as poll watchers. Bobby and I were in charge of the district's largest polling place, PS 282 on Sixth Avenue in Park Slope. The enthusiasm for Chris of the voters on their way to vote was palpable. It was so great and vociferous that we actually thought, out loud, that he was on his way to an upset victory. And, therein, lies a lesson to be learned: One in five voted for Chris (he garnered 20% of the vote to 31% for the winner, Yvette Clark). But unlike the other voters, those 20% were energized and enthusiastic voters. They knew who they were voting for and why and they said so! The other candidates' voters were merely going through the motion of voting for Yassky or Clark or Andrews. You might even say their votes were purchased by lavish outlays of money and a deluge of phony election propaganda. The excited and enthusiastic Owens voters form the basis of a grand and powerful movement that can be built and must be built if we are to be victorious in the next election ... indeed, if we are to win any of the battles that lie ahead - in the ballot box or in the street. And that's why I'm not demoralized. The biggest mistake we can make now is to let those supporters fade away back into their individual lives and homes. Contacts must be maintained and built upon. The potential for victory is there. We just have to go out and build on it. And so, depressed? Hell no! Onward, to building that new movement!

Chris greets supporters on election night. Tired but uplifted by the hundreds who participated in the campaign, he vowed that the fight will continue.

Chris greets supporters on election night. Tired but uplifted by the hundreds who participated in the campaign, he vowed that the fight will continue. Jim Brennan, Brooklyn Assemblyman, at Chris' election night gathering. Brennan was among the few elected officials to stand on principle and endorse Chris' campaign for its progressive content. That's a Democrat with SPINE!

Jim Brennan, Brooklyn Assemblyman, at Chris' election night gathering. Brennan was among the few elected officials to stand on principle and endorse Chris' campaign for its progressive content. That's a Democrat with SPINE!